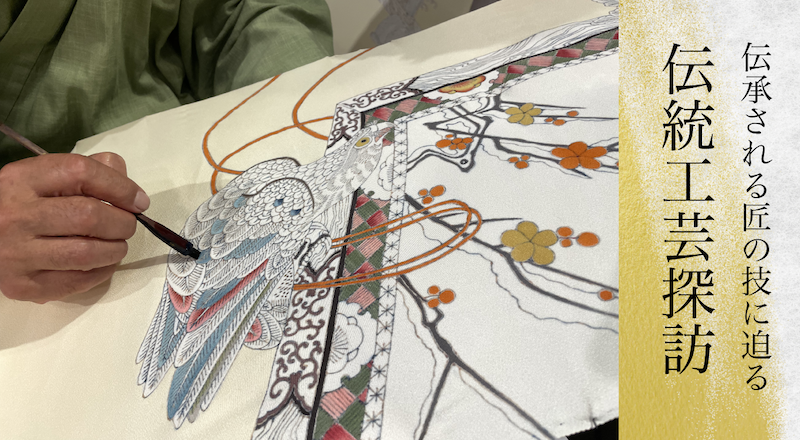

Curiosity and Relentless Effort —

Creating Something from Nothing

in Osaen’s Kimono Making

Yonezawa City in Yamagata Prefecture flourished as a center of silk weaving in the late Edo period. Today, some 30 weaving houses carry on the traditions of Yonezawa-ori. One of the defining characteristics of Yonezawa-ori is that each weaving house showcases its own originality. From yarn preparation to dyeing and weaving techniques, they honor the wisdom of past generations while artisans in their forties and fifties lead a wave of innovation.

“Osaen,” headed by third-generation owner Mr. Sōichi Inomata, is one such house. Believing that “doing the same things as my predecessor would be dull,” he continually challenges himself by developing groundbreaking woven products. In this article, we focus on his signature work “Yuragi-ori” (wavering weave), known for its distinctive gradation and luster, while exploring Osaen’s philosophy toward kimono making.

Two Years in the Making — Questioning Conventions

as the Starting Point for “Yuragi-ori”

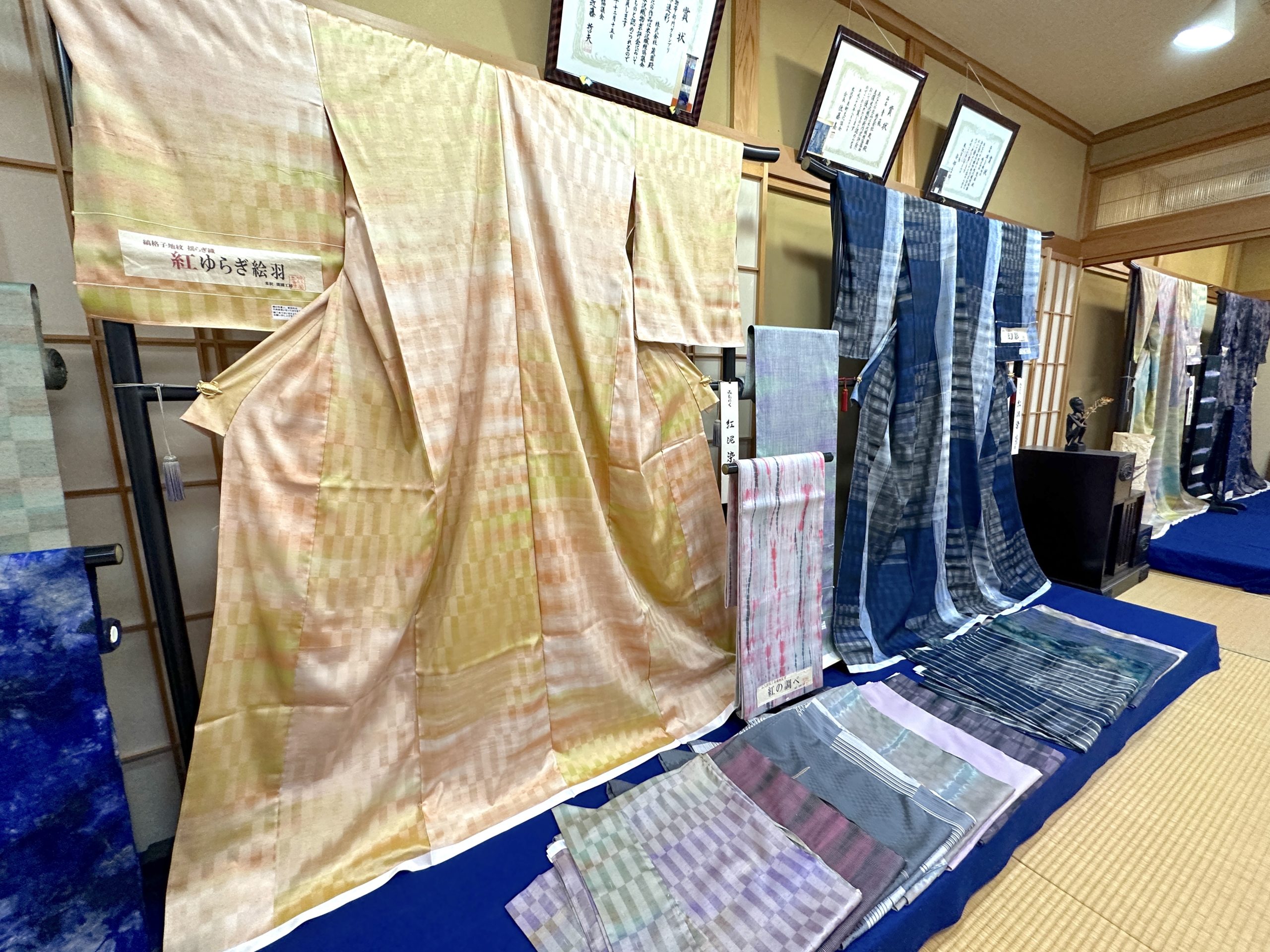

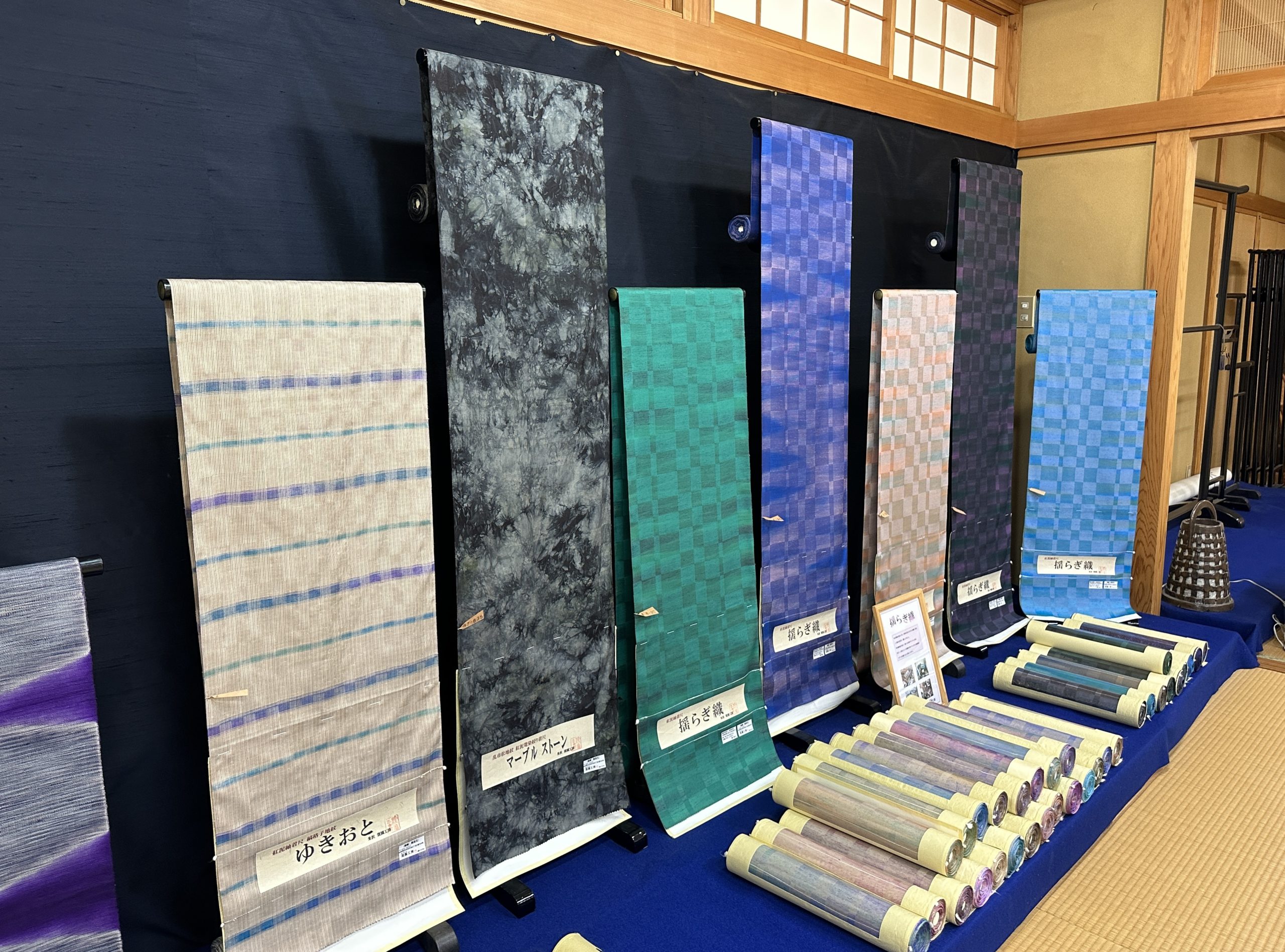

“Yuragi-ori,” a weave that shimmers with elegant luster, is created by using hand-dyed weft threads with unique color gradations, combined with woven ground patterns. The warp threads are a single solid color, yet the interplay with the shaded tones of the weft produces a kimono with subtle, nuanced expression. Along both edges of the bolt, a gradation extends in a triangular form—this is the original technique developed solely by Osaen. The delicate “bokashi” (gradation) effect appears to waver before the eyes, a refinement impossible to replicate elsewhere.

For example, when the warp is in beige tones, the overall impression becomes soft and gentle; when in black, the subdued luster stands out, giving a stylish, modern feel. The ground pattern is not a perfect square “ichimatsu check” (alternating squares in two colors) but a deliberately irregular version, designed to emphasize vertical lines so the wearer appears more slender when dressed.

In fact, “Yuragi-ori” was born after two years of painstaking development. The spark came from questioning an established convention: Why is the standard length of “kaseito” (skein yarn, an essential form for weaving kimono) set according to the traditional shaku measure at approximately 63 cm? That doubt became the starting point for innovation.

If it doesn’t exist, make it myself —

Trial and error leading to a custom yarn winding wheel

“This size was standardized by someone long ago, but it’s actually much wider than the width of a kimono bolt. I began to wonder—wasn’t that just wasteful? So I thought, why not match it to the width of the bolt, at 38 cm,” recalls Mr.Inomata.

In developing “Yuragi-ori,” the greatest challenge, he says, was creating a winding wheel for preparing yarn that matched the width of a kimono bolt. While the circumference of a typical kaseito (skein yarn, an essential form for weaving kimono) winding wheel is 159 cm, Mr. Inomata built his own with a circumference of 94.7 cm. He places the dyed yarn onto this “small winding wheel” to prepare the weft threads that will create the gradation effect. The machine that winds the yarn evenly is from 1950 (Shōwa 25); since replacement parts are no longer available, he fabricates the parts himself whenever repairs are needed.

By matching the width to that of a kimono bolt , he achieved a lighter fabric. But, feeling that a single color lacked interest, he tried dyeing the yarn in two colors—and made an unexpected discovery.

“When I dyed standard-width *kaseito* in two colors and wove them, the result was only a monotonous horizontal stripe. But when I used *kaseito* matched to the width of a kimono bolt, triangular gradations began to appear.”

The Harsh Realities of Hand-Dyeing —

Unforeseen Byproducts Born from Hardship

In “Yuragi-ori,” the balance in dyeing the weft threads is the most critical factor in determining the final appearance. At Osaen, while building on the “color combinations” passed down through generations, Mr. Inomata creates his colors using dye blends measured with his own custom-made “My Spoon.”

“I might mix blue and orange to make black, or blue and yellow to make blue. Making two colors in equal proportions is boring—if I mix them at a 7:3 ratio, I get a yellowish black. I’m constantly exploring the endless possibilities of color combinations.”

One technique that often astonishes visitors is his grueling hand-dyeing process using stainless steel rods. A length of yarn sufficient for one kimono bolt is hung over the rod, and only half is submerged into the dye bath for about 10–15 minutes. Even undyed, the skein for a full bolt is heavy, but once it absorbs the dye, its weight increases significantly. After one side is dyed, the process is repeated for the other—during which Mr. Inomata remains bent forward over the boiling dye bath.

“Summer is hell,” he laughs. “In winter, the workshop can be buried in snow, and there’s a risk of carbon monoxide poisoning, so I have to work with ventilation—my life depends on it. As my arms tire, the rod naturally tilts. You might think, ‘Why not just hang the yarn on something like a laundry pole to make it easier?’ But when the rod tilts, the proportion of the gradation changes—and that can actually create a better pattern. It’s the gift of fatigue. No two pieces ever turn out the same, and that’s the real beauty of hand-dyeing with a stainless steel rod.”

Pursuing a Style of Kimono-

Making Unique to Osaen and Impossible to Imitate

Osaen is known for its bold, high-impact colors—tones closer to those found in contemporary fashion than to the traditional colors used in kimono.

“In the world of craftsmanship, if people look at something and think, ‘We could make that too,’ it has no meaning. I’m always conscious of creating things that can only be made at Osaen—something no other weaving house in Yonezawa or anywhere else could produce. That is how ‘Yuragi-ori’ was born. When it comes to color, I aim for something that kimono enthusiasts will immediately recognize: when they see one of our kimono, they’ll say, ‘That’s the Osaen color.’”

Osaen’s Traditional Dyeing Technique —

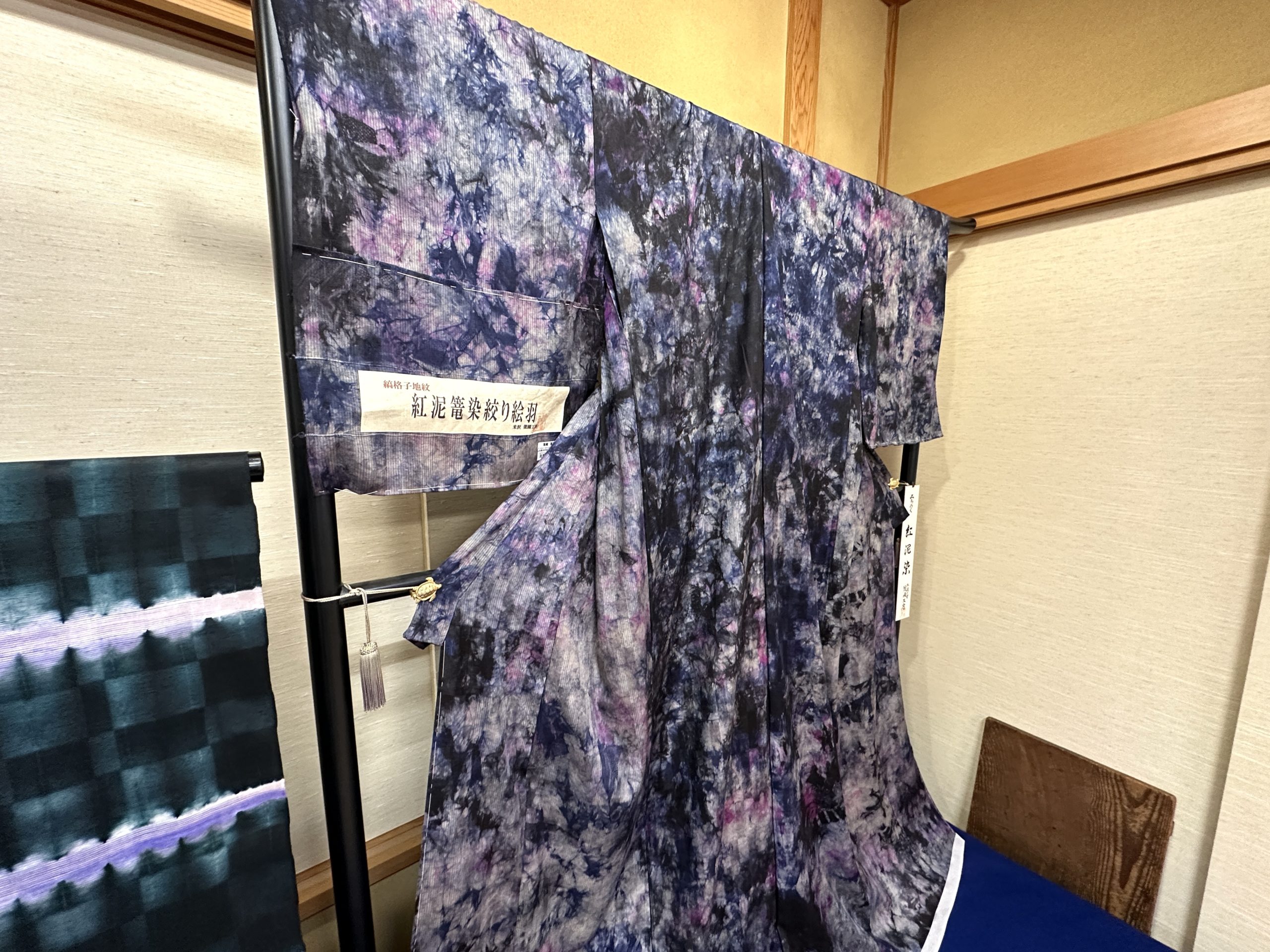

The Unique Texture Born from “Beni-doro-zome” Under-Dyeing

The history of Osaen dates back to the Edo domain period. The name “Osaen” comes from the fact that its weaving house was built on the site of a vegetable garden where produce was once grown for the local lord. The first generation produced numerous tsumugi (a silk textile woven from pre-dyed yarns, known for its unique texture and durability) dyed with safflower. The second generation developed and successfully commercialized beni-doro-zome, an after-dyeing technique using beni-doro—a red clay rich in iron oxide, traditionally used in both dyeing and pottery glazes. Now, under third-generation head Mr. Inomata, Osaen has brought to the world a range of kimono using original dyeing techniques, including “Yuragi-ori,” “Beni-doro Kagozome Shibori” (red clay basket-dye shibori), and “Kukuri Shibori” (bound-resist shibori).

While these works represent Mr. Inomata’s new challenges, they also incorporate techniques handed down from previous generations—most notably beni-doro-zome, a traditional Osaen method blending red clay and safflower dye. This is tradition and innovation in perfect harmony. The secret behind the luster of “Yuragi-ori” lies in this beni-doro-zome.

Using red clay for the under-dye imparts a softness to the fabric and a distinctive glow. Depending on the wearer’s movement or the lighting, the color appears to shift—a hallmark of “Yuragi-ori.” The kimono can also be folded compactly, resists wrinkling, and when spread open, the fabric billows generously with air before touching the floor. The length of time it stays aloft is a clear sign of its remarkable lightness.

Creativity Born from a Spirit of Exploration —

The Distinctive Works of Osaen

Mr. Inomata could be called an inventor of the dyeing and weaving world, handcrafting his own tools and creating something from nothing. He says this ingenuity stems from the fact that his childhood playground was the family workshop, which naturally deepened his fascination with dyeing and weaving.

"It's not something you can do just because you studied design in school, and ideas don’t come just by sitting at a desk. There are so many things you can only discover through trial and error. Thinking, ‘Next time, I’ll try this!’—that’s what makes it so much fun. You couldn’t do that in a divided workflow,” says Mr. Inomata, his eyes sparkling like an excited boy.

The kimono created by Osaen are filled with originality born from a spirit of exploration. The inventive challenges of Mr. Inomata are ones to watch closely.

See Also : The Textile Encyclopedia / Yonezawa-ori & Yonezawa-tsumugi (Yamagata Prefecture)”

See Also : “Exploring the Allure of Yonezawa-ori Vol.1 / Nitta”

See Also : “Exploring the Allure of Yonezawa-ori Vol.2 / Sashime Orimono”

See Also : “Exploring the Allure of Yonezawa-ori Vol.3 / Konken Orimono”

Osaen

5-2-104 Chūō, Yonezawa-shi, Yamagata Prefecture, Japan

TEL:+81-238-23-6001