Production Area: Tokyo

Rooted in the sophisticated world of Edo-period merchant culture, Tokyo hand-painted Yuzen stands in contrast to the opulence of Kyoto Yuzen. Known for its subdued color palettes and stylishly understated motifs, this tradition carries an air of urban chic. Today, Tokyo’s dye artisans continue to honor classical designs while embracing modern sensibilities, creating works that bridge past and present. As an art form deeply tied to city life, Tokyo Yuzen continues to captivate with its quiet elegance and creative evolution.

In This Article:

- The history and key features of Tokyo hand-painted Yuzen, born from Edo’s merchant culture.

- How it differs from Kyo-yuzen: calm colors and refined, urbane motifs.

- Contemporary examples and the artisans behind the tradition.

- The growing relevance of Tokyo Tegaki-yuzen in today’s lifestyle and fashion.

Yuzen dyeing is said to have originated during the Kyōhō era (1716–1736) of the Edo period, created by a painter from Kyoto. As Edo became the political center of Japan, dyeing artisans and painters migrated to the city, leading to the development of Tokyo Tegaki-Yuzen. Alongside Kyo-Yuzen and Kaga-Yuzen, it is now considered one of the three major styles of Yuzen dyeing in Japan. In 1980, it was officially designated as a traditional craft of Tokyo.

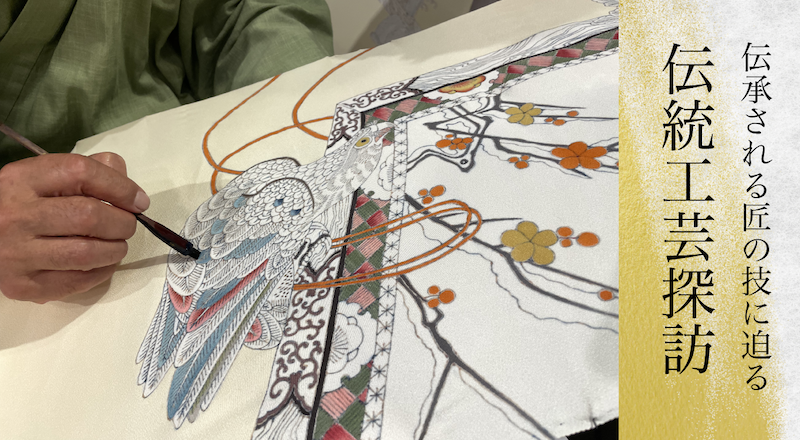

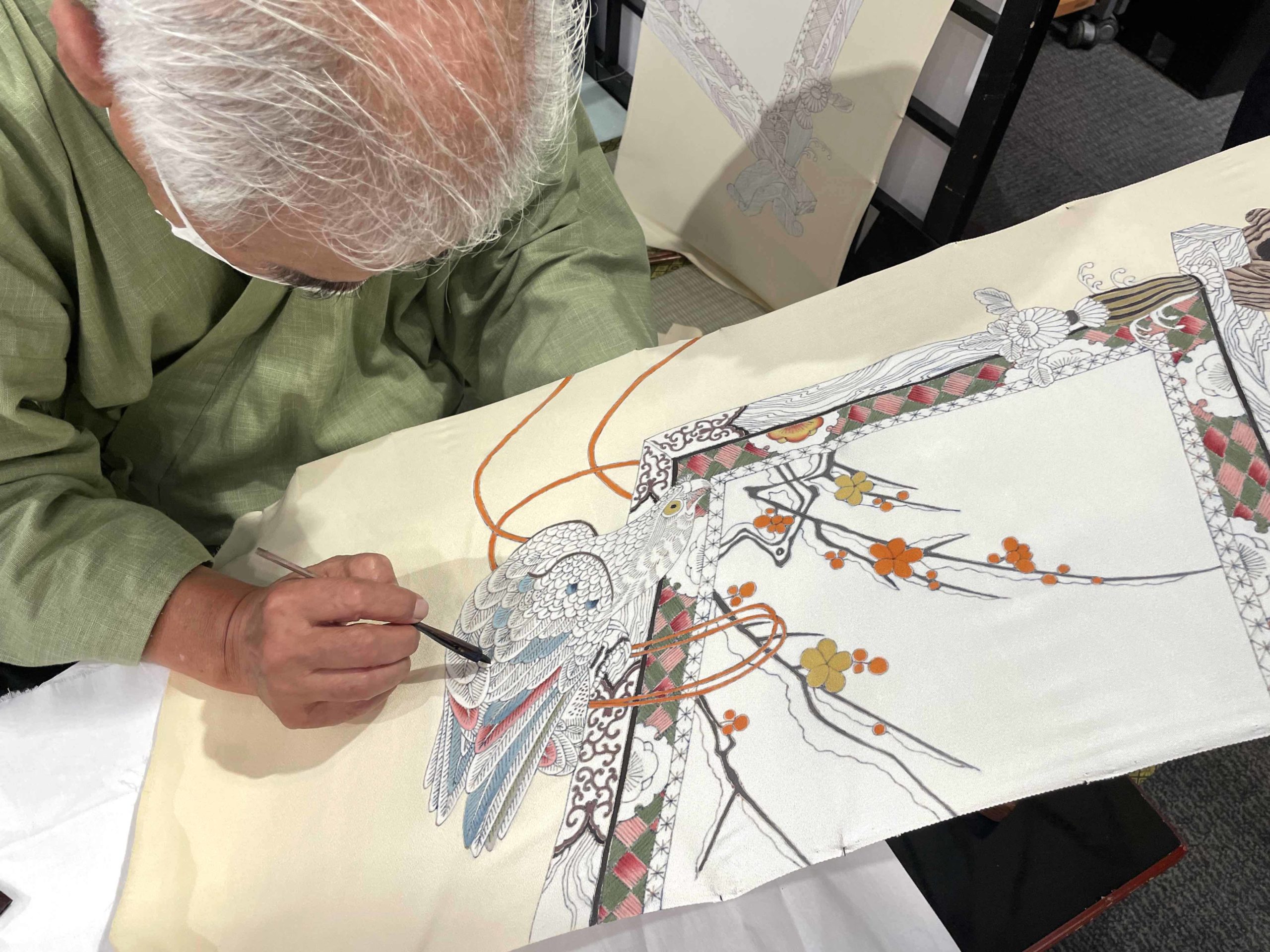

In this feature, we explore the unique charm of Tokyo Tegaki-Yuzen, which has woven its tradition through distinctive colors and patterns rooted in Edo’s merchant culture. We visited the atelier of Mr. Susumu Iwama, a certified traditional craftsman and president of the Tokyo Tegaki-Yuzen Traditional Crafts Association.

Tokyo Tegaki-Yuzen: Refined Colors Rooted in Edo Aesthetics

Kyo-Yuzen is known for its opulent beauty and rich colors, while Kaga-Yuzen features natural motifs rendered in traditional Kanazawa hues. In contrast, Tokyo Tegaki-Yuzen has developed with a focus on expressing *wabi-sabi* — the quiet, refined aesthetic of simplicity and impermanence. During the Edo period, sumptuary laws prohibiting luxury restricted the number of colors allowed in kimono. This limitation ironically led to a rise in appreciation for Edo-style sophistication, characterized by subdued grays and blues. The designs often depicted scenes of Edo, strongly reflecting the spirit of *iki* (chic elegance).

Mr. Iwama explains, “Because the Yuzen technique arrived in Tokyo later than in Kyoto or Kanazawa, there’s a greater sense of creative freedom here. The patterns are often more modern and varied. While Tokyo Yuzen was once firmly categorized under wabi-sabi, exchanges with Kyoto and Kaga in recent years have blurred those stylistic boundaries. Personally, I tend to use classical colors that are brighter rather than muted, and many people appreciate this as the 'Tokyo color palette.'”

Over 2,000 Yuzen Artisans Once Worked in Tokyo

Mr. Iwama was destined to enter the world of Yuzen dyeing from a young age, as his family operated a specialized workshop for *norioki*, the resist-paste application process essential to Yuzen. By the time he was in junior high school, he had already decided on his path. He went on to study dyeing techniques in high school and, after graduation, apprenticed under a master known for his skill in traditional Japanese painting and classical designs. He lived and trained with the master, learning every aspect of the craft.

“At the time, some studios had enough apprentices to form a baseball team,” he recalls. “Even within the Tokyo Craft Dyeing Cooperative, there were around 500 registered artisans. Including the unregistered ones, there were over 2,000 people involved in Yuzen work.”

However, following the oil crisis and resulting economic downturn, demand in the market declined, leading to a reduction in work.

“During the peak, the process was divided among specialists, but to survive in changing times, it became more practical for one artisan to handle multiple steps—such as sketching, color application, and dyeing—rather than relying on division of labor.”

"My work is 90% commissions, and even at 70, I’m fortunate to still be busy."

The Many Traditional Techniques Behind Tokyo Tegaki-Yuzen

Created through numerous manual processes, Tokyo Tegaki-Yuzen is a uniquely Japanese dyeing technique that decorates fabric as if painting a picture. From the initial concept to the final touches, the process is broadly divided into twelve distinct steps.

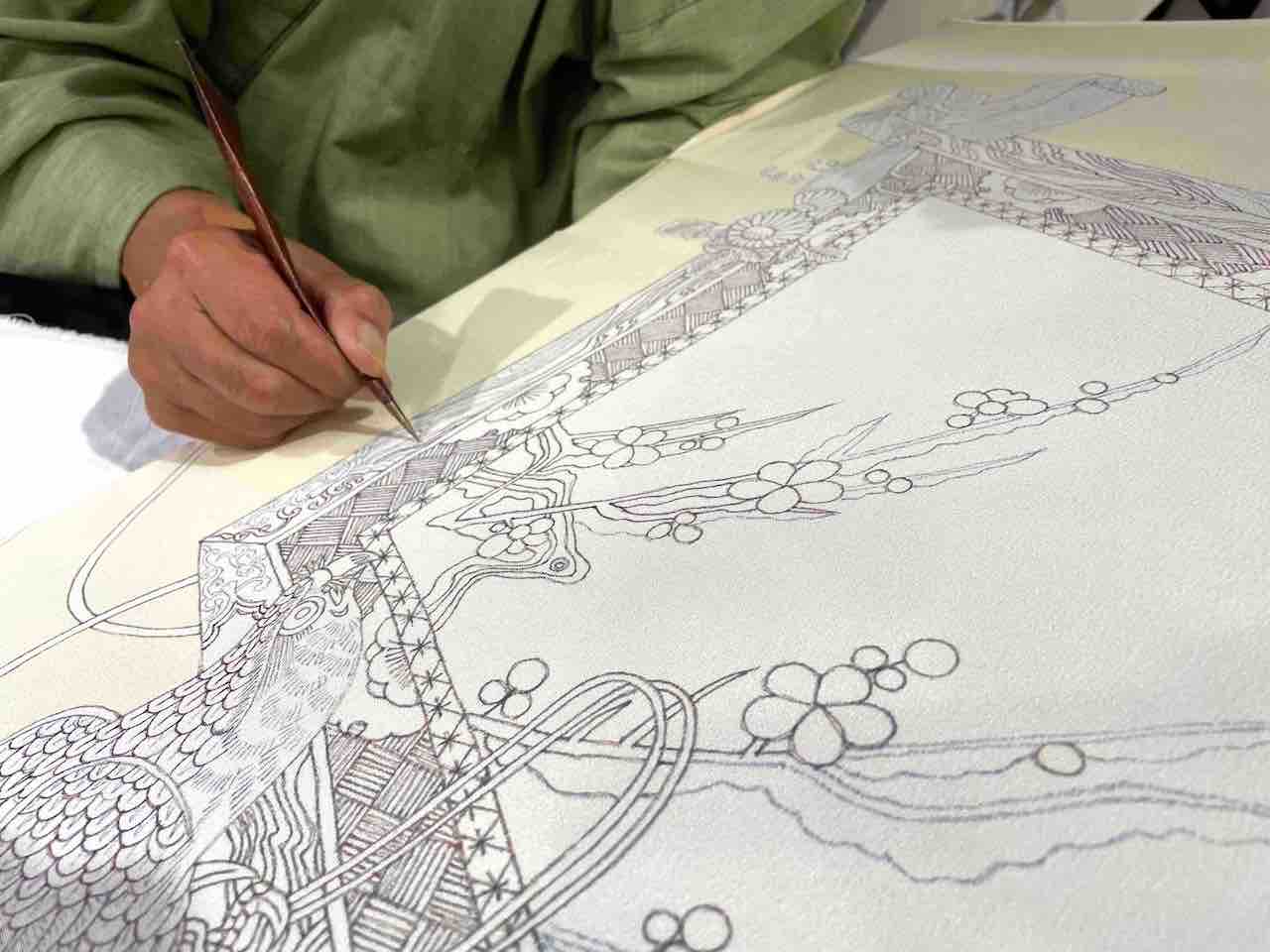

It begins with the sketching stage. On white fabric or “tsukesage” (a type of kimono with patterns that are aligned to create a continuous design when worn), the artist draws the outline of the planned design. This is done using a brush dipped in aobana, a blue liquid extracted from the Asiatic dayflower, which disappears when washed with water.

Next is “itome-norioki” (a resist-paste outlining technique using fine lines to separate design areas before dyeing), in which a fine paste is squeezed out along the outline and used to cover areas within the design. This paste, made from glutinous rice flour, rice bran, and a pinch of salt, is applied using a cone-shaped tool made from paper. The fine lines remain white after dyeing, resembling thin threads—hence the name “itome,” meaning thread-like. In traditional practice, a reddish tint made from suō (a dye from sappanwood) is added to make the outlines more visible.

Once the paste has been firmly adhered to the fabric—a step called “ji-ire”—the process moves to **hand-painted Yuzen coloring**. Here, brushes and fine tools are used to carefully fill in the design with vibrant dyes inside the resist outlines.

Following this is “hikizome” (a dyeing method where large areas of fabric are evenly brushed with color), which applies the background color across the entire fabric. The work then proceeds through steaming, mizumoto (rinsing and setting the dyes), and “uwayu-noshi”, a heat process to smooth and shape the fabric.The final stage, called “finishing,” may include embroidery, gold foil, or other embellishments. Known as “kinsai”, this process involves adhering gold or silver leaf or gold powder to the dyed fabric. It is applied based on the formality of the kimono and the balance of the overall design.

Masterful Artistry Dazzling Gold Techniques

There are various techniques for gold decoration. On this occasion, Mr. Iwama demonstrated a method in which adhesive is applied to specific areas, and gold foil is carefully laid on top. Since the foil is extremely delicate and easily blown away, the process must be done in a windless environment—even in summer.

Mr. Iwama’s favorite foil tweezers have been in use for over 40 years. They were passed down to him by his master when he became independent.The piping cone shown here is used when adding fine gold lines to the design. It’s made of traditional Japanese paper coated with persimmon tannin. The thinner the gold lines, the more refined the finish appears, and Mr. Iwama has a wide range of tips in different sizes to achieve that level of elegance.

Passing Traditional Craftsmanshipon to the Next Generation

While the kimono industry as a whole is facing serious challenges with succession, Mr. Iwama notes that Tokyo tegaki yuzen (hand-painted yuzen) is seeing an inspiring rise in the number of female artisans.“Taking on multiple stages of the process alone requires a great deal of tools, materials, and skills,” he explains. “Even so, it's encouraging to see young artisans embracing the craft with such dedication. Alongside passing down the techniques, I also make a point to share the appeal of Tokyo tegaki yuzen with the next generation—especially children—through hands-on dyeing workshops and other outreach efforts.”

Pictured here is a furisode titled “The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter” by female artisan Ms. Tamaki Ueda, who received the Director-General’s Award from the Kanto Bureau of Economy, Trade and Industry at the 58th Dyed Art Exhibition Competition.Commenting on the work, Mr. Iwama says, “This design skillfully interprets Japan’s oldest literary tale with a modern sensibility. While retaining the celebratory vibrancy of the furisode, the controlled use of color and tone creates an elegant calm—something that truly reflects the aesthetic of Tokyo tegaki yuzen.”

In recent years, new dyeing technologies such as inkjet printing have broadened the methods available. However, the depth, dimension, and subtle nuance unique to hand-painted works remain an irreplaceable joy—something only the artisan’s hand can achieve. The radiance rendered on silk, like a piece of fine art, continues to shine, passed on through the hands of masters like Mr. Iwama and the new generation of artisans following in his footsteps.

See Also : The Textile Encyclopedia | Tokyo Tegaki Yuzen(Tokyo)

Mr. Susumu Iwama,/Tokyo Tegaki Yuzen Artisan

Chairman, Tokyo Association of Craft Dyeing and Weaving Cooperatives

President, Tokyo Tegaki Yuzen Traditional Craftsmen’s Association

Vice President, Japan Association of Traditional Craftsmen

President, Kanto Traditional Craftsmen’s Association

Tokyo Association of Craft Dyeing and Weaving Cooperatives

3-21-6 Naka-Ochiai, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan

Tel: +81-3-3953-8843

Official Website>>