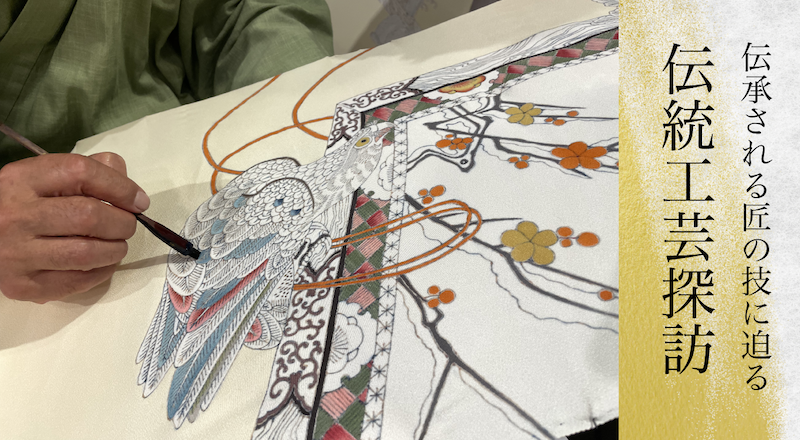

In this feature, we speak with Mr. Katsuyoshi Ise, a certified traditional artisan and instructor at the Oshima Tsumugi Technical Training Institute operated by the Amami Oshima-tsumugi Association. He shares insights into the highly advanced weaving techniques required for this renowned textile.

In This Article:

- The beauty of Oshima Tsumugi woven by many skilled hands.

- Kasuri patterns created through the unique shimebata process.

- Various dyeing styles including indigo mud-dyeing.

- A training ground for future Oshima Tsumugi artisans.

- Preserving craft and culture through education.

Refined Kasuri Patterns

and a Silken Touch Born from Many Hands

Revered as the “queen of kimono,” Oshima-tsumugi from Amami is designated by Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry as a Traditional Craft. Every step—from warping to kasuri patterning, dyeing, and weaving—is done by hand. With more than 38 intricate processes involved, it can take anywhere from six months to a full year to complete a single roll of fabric. The result is a textile of extraordinary craftsmanship and understated elegance.

The most iconic feature of Oshima-tsumugi is its intricate kasuri (ikat) patterns. Unlike typical textiles, it involves two separate weaving processes. Before the final weaving (seishoku), there is a preliminary process using a loom called shimebata, where threads are bound to resist dye and create the precise kasuri patterns.At the Oshima-tsumugi Technical Training Institute, operated by the Amami Oshima-tsumugi Cooperative, artisans are trained in both shimebata and final weaving techniques. Each process requires extraordinary precision and patience.At the Oshima-tsumugi Technical Training Institute, operated by the Amami Oshima-tsumugi Cooperative, artisans are trained in both shimebata and final weaving techniques. Each process requires extraordinary precision and patience. Observing these steps firsthand offered a renewed appreciation for the extraordinary skill and dedication behind this traditional art.

Intricate Kasuri Patterns Woven Through

Oshima-tsumugi’s Unique “Shimebata” Process

The patterns of Oshima-tsumugi are created through kasuri (ikat) dyeing techniques that involve resist-dyeing the threads before weaving. A cotton warp is stretched, and silk threads are woven in as the weft to create a structure called kasuri mushiro (kasuri mat). After dyeing, the mat is carefully unraveled to extract the dyed silk threads, which are then used in the final weaving process.

As we stepped through the doors of the academy, a sharp crack rang out across the room. It was the distinctive sound of a shimebata loom at work, used in the kasuri (ikat) preparation process. Unlike the gentle rhythm one might associate with handweaving—passing the shuttle through the warp and tapping the weft into place with a heddle—the shimebata produces a more forceful and precise sound. This loom serves a different purpose altogether, one that speaks to the extraordinary precision behind Oshima-tsumugi’s intricate patterns.

We observed that the artisans were using an unusually long shuttle—nearly the width of the weaving surface itself. They would strike the shuttle forcefully with the kamachi (a type of beam) in one powerful motion. To ensure maximum impact, the loom was even equipped with an air assist mechanism, making the sharp, cracking sound all the more understandable. According to Mr. Katsuyoshi Ise, a certified traditional artisan and instructor at the academy, such intense striking is essential. Without this level of tension, the resist dyeing on the threads would not take hold properly.

In the past, Amami Ōshima used hand-tied resist dyeing for its kasuri threads, much like Yūki Tsumugi. But in 1902, the invention of the shimebata (binding loom) revolutionized the process, allowing artisans to weave the resist pattern instead of tying it by hand. The warp threads on the shimebata are made from cotton that has been heat-treated in a gas furnace to remove surface fuzz, creating a smooth base. Onto this warp, silk threads—destined to become the actual kimono fabric—are woven as weft. The woven areas effectively act as tied sections, creating resist zones that can be dyed. This is why people say, “Ōshima Tsumugi is woven twice.”And Mr. Ise explains “Such intricate kasuri patterns could never be achieved through hand-tied resist techniques, where threads are individually tied to prevent dye penetration,”

Although the shimebata shares its basic structure with the common upright takabata loom, there is one major difference: its sheer size and weight. Because the shimebata requires the shuttle to be struck with full force using the kamachi, the loom must be extremely sturdy and heavy. If it were light, it would shift out of place. Even with casters attached, it reportedly takes four adult men to move one. While the addition of an air compressor has made the process accessible to women as well, the task is still widely considered “men’s work” on the island, and most shimebata artisans are male.

Admiration for the Intricate

Craftsmanship of Oshima-tsumugi

The guiding template for the shimebata process is a design sheet marked with dots over a grid, indicating the exact pattern to follow. Artisans must weave each line precisely according to the diagram to create the kasuri pattern. Depending on the design, it takes between 200 to 300 repetitions of this process just to prepare the weft threads for a single kimono. In the era when Oshima Tsumugi was produced at scale, twenty threads were bundled together to process kasuri yarns for twenty bolts of fabric at once. “The shimebata was developed as a method to produce finer patterns in greater quantities,” explains Mr. Ise.

Mr. Ise was born into a family of weavers and has been involved in the family business for over fifty years, starting from early childhood. Because his family workshop was located in a rural area and was relatively small, it did not rely on the typical division of labor found in larger weaving houses. Instead, they handled nearly every process in-house—from winding the yarn and applying paste, to kasuri processing with the shimebata loom, dyeing other than mud-dyeing, and weaving. Mr. Ise thus became well-versed in all stages of Oshima Tsumugi production.

“If I didn’t do yarn winding, I wasn’t allowed any pocket money,” he recalls with a laugh. “It was in high school when my father encouraged me to start working on the shimebata loom.”

Studying under the expert guidance of Mr. Ise is Mr. Higashi, who hails from Yokohama in Kanagawa Prefecture. After studying fashion design at university and working as a schoolteacher for three years, he decided to pursue something truly unique—something that couldn’t be easily replicated. Three years ago, he moved to Amami Oshima to study the art of Oshima Tsumugi.

“I majored in pattern making at university, and even then, I was drawn to the extraordinary level of craftsmanship behind authentic Oshima Tsumugi,” he explains. “It’s unlike anything else.”

Although he first came to Amami with a light-hearted spirit of “let’s just give it a try,” he is now fully committed to mastering the shimeori (warp kasuri weaving) technique and hopes to turn it into a lifelong profession. His skills are steadily improving—so much so that the teachers at the academy are now using the warp threads he prepares in their own weaving. It is clear that Ms. Higashi has earned the trust and admiration of those around her as a promising young artisan.

Kasuri Threads Enter the Dyeing Process

Infused with a Variety of Traditional Techniques

Once the kasuri mushiro (kasuri straw mat) is completed, it moves on to the dyeing process. The sections that were tightly woven on the shimebata remain undyed, while the rest absorb the colors. The traditional method known as mud-dyeing involves repeatedly soaking the threads in dye from the techi wood and local mud to create the signature deep black-brown hue. In addition, other methods have emerged—such as mud-ai Oshima, where the threads are first dyed in indigo before undergoing mud-dyeing, and iro-Oshima, which uses chemical dyes to produce brighter tones. In some cases, colorful motifs appear in limited areas. These are created by temporarily unraveling part of the kasuri mushiro and applying chemical dyes directly onto the threads.

Even mud-dyeing alone requires 70 to 80 repetitions of hand-dyeing the threads with techi wood and mud. Thus, it is not only the weaving, but also the dyeing process that is incredibly detailed and painstakingly done by hand.

The Intricate Hand-Weaving

That Brings Oshima-tsumugi to Life

You might think that once the kasuri yarns are prepared, the rest is simply weaving—but in the case of Oshima Tsumugi, the process remains just as meticulous. The key lies in kasuri alignment. “If the dots on the warp and weft kasuri threads don’t match perfectly, the entire pattern will be off,” explains Ms. Natsuyo Sakae, an instructor who has been weaving Oshima for over 65 years.“After weaving about 5 to 7 centimeters, we loosen the warp threads and adjust the position of the weft threads using a needle, aligning the kasuri pattern precisely.”

“The tension of the warp and the pressure applied to the weft both affect where the threads settle. So the key is to weave with a balance that naturally allows the kasuri to align—but that kind of balance is something you can only develop through your own sense and experience. As we weave while making these adjustments, we also use a needle to make millimeter-level refinements at the very end.”

When Ms. Natsuyo Sakae—now a certified Traditional Crafts Artisan in the weaving division—first began weaving in the mid-1950s, Oshima Tsumugi production was at its peak.

She hails from Tatsugō, a region of Amami Ōshima known for its thriving textile culture. At the time, it was common for households to have two or three looms, and weaving huts equipped with ten looms each were shared within villages.

Despite her parents urging her to continue her education, Ms. Sakae chose a different path, leaving junior high school to pursue weaving. As of the 2024 interview, she had been teaching at the institute for eight years.

“I learned the craft almost without realizing it,” she reflects with a gentle smile.

“But as I began teaching others, I’ve come to recognize just how advanced and demanding these techniques truly are. I always encourage my students, telling them, ‘Once you learn this, it’s yours for life.’”

Among her students are high school graduates, mothers balancing child-rearing with classes, and people of all ages.

“What brings me the greatest joy,” Ms. Sakae adds, “is seeing young people taking part in preserving this tradition.”

In the weaving hall of the institute, filled with natural light from many windows, ten looms stand in neat rows. Seven students were immersed in weaving Oshima Tsumugi, each working on textiles for different member companies of the cooperative. While learning at the institute, they are simultaneously training as future artisans. The textiles on the looms vary—from traditional tortoiseshell (kikkō) motifs to white Oshima and colorful patterned pieces—each with its own charm. And yet, every student shared the same sentiment: “It’s difficult, but enjoyable.” It seems that Oshima Tsumugi not only uplifts those who wear it but also those who weave it.

Once the weaving is complete, each bolt of fabric undergoes a rigorous 24-point inspection conducted by the cooperative. Only after passing this evaluation is it granted the official Earth Mark certification seal—an emblem of quality—before it is shipped out into the world. Meticulously crafted through the hands of countless artisans on Amami Ōshima, Honba Amami Ōshima Tsumugi is truly one of the finest textiles Japan has to offer.

See Also : The Textile Encyclopedia | Amami Oshima-tsumugi (Kagoshima Prefecture)

____________________________________

Honba Amami Ōshima Tsumugi Technical Institute

(Inside Honba Amami Ōshima Tsumugi Cooperative)

48-1 Urajōchō, Naze, Amami City, Kagoshima Prefecture

TEL: +81-997-52-3411

Official Website>>

__________________________________

Text & Interview by Miki Shirasu